In this time and age, there is a concretely increasing risk for Product teams to become bottlenecks and innovation blockers: but with that risk come massive opportunities.

Since the introduction of generative AI into mainstream software development, the debate has centered on what it means for the future of engineering. Early predictions suggested that models would soon reach a level where they could replace human programmers entirely: machines programming machines.

Three years on from ChatGPT’s release, that vision looks increasingly unlikely. Coding agents are highly effective at producing code quickly, but unguided they generate results that are brittle, insecure, and difficult to scale or maintain.

What has emerged instead is a different dynamic: software engineers have taken note of the new possibilities, and by combining engineering fundamentals with careful system and architecture design they have found ways to harness these tools effectively. The most successful approach has been to break problems into small, self-contained units, write detailed specifications (leveraging as well dedicated planners), and feed those into coding agents. The result is more focused, context-aware outputs that align with production requirements.

In this environment, senior engineers thrive. Staff and Principal engineers, in particular, can translate complex business goals into clear, technical specifications and then accelerate implementation with AI. Their role as system designers has become even more central, while the tools serve as force multipliers.

A shift in assumptions

This shift has important implications for how organizations operate, especially in relation to product management.

Historically, every line of code was seen as a liability. Software was expensive to build and maintain, so product teams were tasked with identifying priorities and minimizing unnecessary work. Their role was to ensure that scarce engineering capacity was invested in the features that mattered most.

That assumption no longer holds. In 2025, code is comparatively cheap to produce. A senior engineer can now deliver in a weekend what once required a small team several weeks. Prototyping in production has become faster and more accessible, and the space for experimentation has grown exponentially.

As Stanford Professor and former Google Brain scientist Andrew Ng has pointed out, this creates a critical bottleneck: product teams that have not evolved at the same pace as engineering now risk severely slowing down innovation. When building software is no longer the scarce resource, the value of product shifts.

The role of specifications

For many product managers, the phrase spec-driven development will trigger instant resistance. It evokes the era of waterfall processes and heavy documentation. But in practice, the new form of spec-driven work looks very different.

Specifications today are concise, evolving, and essential. They function more like user stories and acceptance criteria, formats Agile teams leveraging GenAI already use. What has changed is their weight: precise specs now determine whether AI coding agents can produce reliable, production-grade code or whether they collapse into noise.

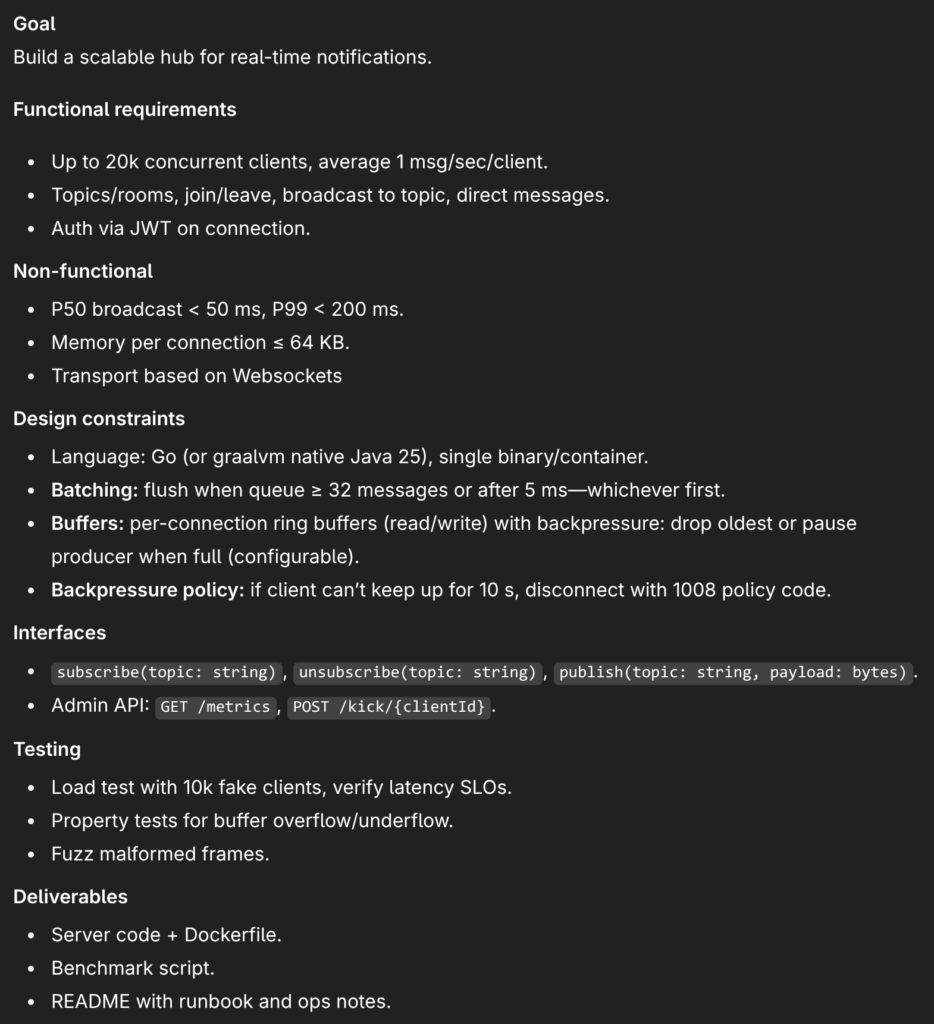

Example:

You can instruct the likes of openai codex, claude code, gemini cli : “Implement this plan step by step. First scaffold the project and interfaces; stop and show me the file tree. Next, implement ring buffers and unit tests. Next, implement the hub and batching…” and so on.

Specs are therefore no longer administrative paperwork but the core of the development process, and without them engineers lose productivity gains, AI produces fragile results, and organizations lose speed and money.

The future of product and engineering

When code becomes cheap to generate, the scarce skill is no longer implementation but the ability to specify what should be built and how it should behave. Engineering is becoming faster than Product teams ability to decide, and the net result is organizations where the pace of innovation is dictated not by technical capacity, but by indecision and misaligned priorities.

This is where the boundary between product and engineering begins to blur and merge.

The emerging role is someone who can synthesize business needs and technical design into clear, machine-readable specifications. That skill enables the effective use of generative coding assistants and unlocks significant productivity gains in engineering teams.

This should unsettle traditional product managers. The function cannot continue as it did when software was scarce and expensive. If product continues to operate as a layer that translates vague business needs into vague outcomes or worse sterile backlogs, it will simply get bypassed. Engineers who can gather requirements and write specs directly will move way faster.

The convergence of product and engineering is not theoretical and it is already happening inside high-performing teams. The people who thrive are those who understand business context deeply and can express it as precise technical intent: everyone and everything else risks becoming simply an obstacle. If you cannot write precise, testable, AI-ready specifications you are not guiding your team anymore, but slowing it down.

The end of product, at least the way we know it, is not about titles disappearing, but about accountability shifting. In a world where code is cheap, the value lies in clarity of intent and precision of design. That is the work now, and to not become a bottleneck, Product will have to reinvent itself and take note too.