Implications for the conversation about AGI feasibility

Many modern thinkers — from physicists to philosophers — see the universe fundamentally as an informational structure. Every particle, field, and interaction can be described as information embedded in the fabric of reality.

At the physical level, “information” is the distinction, actual or potential, between possible states of a system, which reduces the uncertainty about which state is or would be observed. It is always embedded in matter, energy, or fields, never “floating” without a physical substrate. In classical physics this distinction concerns determined states, while in quantum physics it concerns probability distributions described by the wave function. In classical physics, information is quantified as a reduction in entropy (uncertainty), measured in bits; in quantum physics, it is expressed through the von Neumann entropy of a quantum state. Landauer’s principle reminds us that erasing even a single bit of information has an irreducible physical cost in energy, making information as concrete and subject to the laws of nature as mass or energy itself.

In this perspective, most processes are objectively describable: we can measure them, model them, and predict them from an external point of view.

But consciousness — and in particular self-awareness — is something fundamentally different.

Unlike stars or quarks, consciousness has a first-person dimension. It is not just a set of states to be measured: it is experienced from within.

The taste of chocolate, the redness of the color red, the pain of a broken limb — these subjective experiences, defined as qualia, cannot be fully translated into objective, third-person terms.

Even if we mapped every neuron that activates in a brain, the resulting data could not objectively describe the feeling of being oneself or of feeling pain. By looking at that data I would not feel pain, nor could I have the same sensory experience of seeing the color red. Crucially and by analogy then, a machine merely replicating a perfectly detailed brain configuration would not be able to feel, or to be¹.

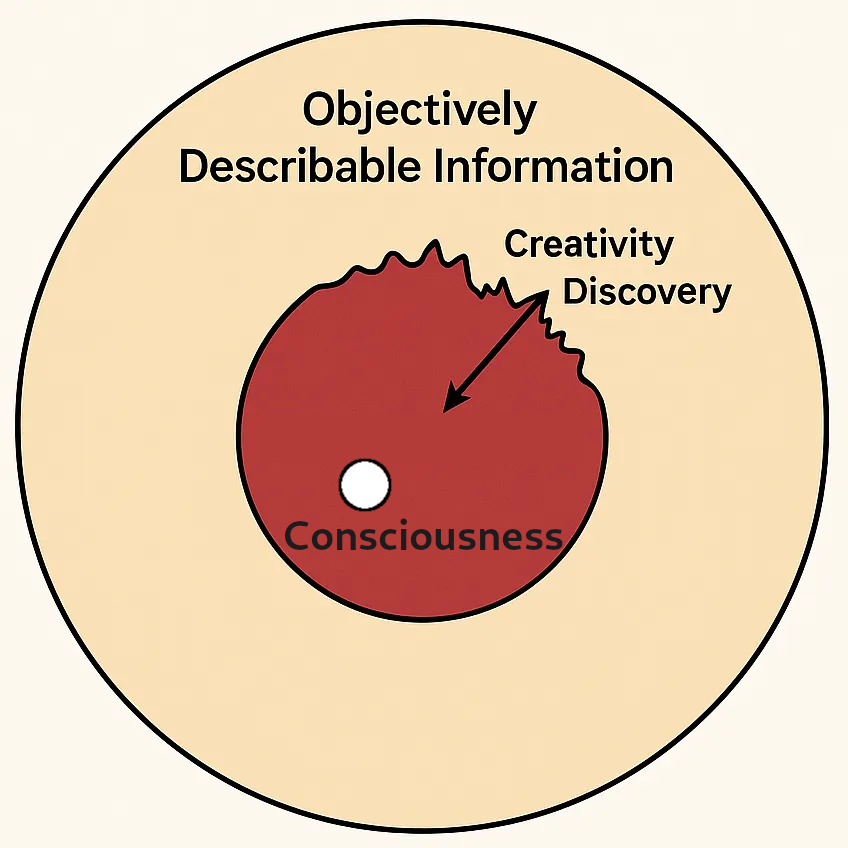

This creates a category boundary in the informational landscape of the universe: on one side objective information (completely describable from the outside), on the other subjective experience (irreducible, self-contained, and accessible only to the one who lives it).

From this perspective, self-awareness is a singularity in the space of information — a point where the usual mapping from system to description breaks down.

And this concept is very important to understand in today’s landscape of discussions about general artificial intelligence.

Self-awareness is not just a philosophical curiosity: it is a cognitive enhancement.

It allows a mind to model itself as an agent in the world, to imagine alternative versions of reality (including hypothetical futures), and to create a mental space where distant ideas can meet and merge.

That is why human beings can do more than just react to the world: we can create and discover.

We are not limited to optimizing within fixed rules; we can invent the rules themselves.

Qualia, subjective experiences, could even play a role in this process: emotional sensations of excitement, elegance, or beauty can guide the ideas we choose to pursue. When it comes to artistic creativity, qualia probably give humans an advantage.

But is this also true for abstract creativity — for example, discovering new branches of mathematics or physics?

A well-designed AI could, in principle, surpass us if it managed to escape the recombination trap: most current models recombine patterns learned from training data without venturing into truly unexplored territories.

To avoid this, an AI dedicated to discovery should have a few things:

Formal self-consistency checking — the ability to mathematically prove or disprove its own hypotheses.

Model-driven exploration — generating and testing rules for hypothetical universes.

Meta-learning — not only learning instances of physics/mathematics, but learning how to create new formalisms.

Intrinsic curiosity — seeking novelty and informational gain beyond the training data.

Humans still have an advantage in semantic leaps: the ability to spot a deep pattern in one domain and transfer it to another (as in bringing group theory into particle physics).

We are also good at completely abandoning old frameworks when they stop working — a radical flexibility that is hard to program.

Perhaps a future AI, with symbolic reasoning, generative creativity engines, and experimental feedback (real or simulated), could explore the space of mathematical and physical possibilities much faster than we can.

It might lack the singularity of subjective experience, but it could still surpass us in terms of pure discovery.

However, this will not happen until further discoveries in physics, biology, and philosophy of mind lead to a radical paradigm shift in the construction of artificial minds.

Some hypothesize, for example, that the brain — or even the universe itself — functions like a quantum computer, capable of exploring multiple possibilities in parallel and “collapsing” the answer in a single instant, making it available to the mind.

If the universe is a sea of information that is currently or potentially measurable, then consciousness is the only island where the map and the territory coincide — where the system observes itself from within.

This singularity gives rise to our ability to create, imagine, and discover new truths about the cosmos.

The question is whether artificial minds, even without the inner light of self-awareness, can learn to navigate — and perhaps to extend — the boundaries of that sea.

¹ This is called the Hard Problem of Consciousness, which I will tackle in more detail in the second article of this series.

For those interested in exploring further:

Wheeler, J.A. (1990). Information, Physics, Quantum: The Search for Links.

Lloyd, S. (2006). Programming the Universe.

Fredkin, E. (1990). Digital Philosophy.

Shannon, C.E. (1948). A Mathematical Theory of Communication.

Landauer, R. (1961). Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process.

Nagel, T. (1974). What is it Like to Be a Bat?

Chalmers, D. (1995). Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness.

Weizsäcker, C.F. von (1971). The Unity of Nature.

Penrose, R., & Hameroff, S. (2014). Consciousness in the Universe: A Review of the ‘Orch OR’ Theory.