Introduction

In my previous article, I took an implicit stance in the debate on self-awareness. I argued that even a perfect brain replica — implemented as a machine, mimicking every connection and signal — would not feel, nor be. In doing so, I brushed against what philosophers call the hard problem of consciousness: why and how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experience.

On this problem, two broad schools of thought face each other:

One argues that structure and function are enough. If the causal architecture of the brain is replicated — whether in neurons, silicon, or even sticks arranged as zeros and ones — consciousness will necessarily emerge. In this view, the “stuff” doesn’t matter: it’s the organization that counts.

The second holds that qualia and consciousness are intangible, irreducible to any description or mechanism, and thus not “cageable” in any model or physical instantiation. In this vision, structure does not imply emergence. Even if we capture every detail of a brain in silicon, we may still be left with nothing more than a sophisticated zombie: outwardly functional, inwardly empty.

My own position is more nuanced, and it has shifted over time. I do believe that consciousness emerges from biology — that the living brain produces awareness as part of its nature. What I am not convinced of is that mocking brains with abstract neural networks or even perfect simulations would inevitably bring us to the same place.

This reflection is not purely theoretical. It has been with me for decades, resurfacing in conversations, in books that marked me, and nowadays in the presence of artificial intelligence and large language models. It has been a real journey with some distinct phases that shaped my thinking.

Prelude – Summer 1987

My fascination with these topics is as old as my love for computing. It was a hot summer in 1987, when I first laid hands on my new Commodore 128.

I was utterly fascinated by its possibilities. I devoured books and magazines about programming, assembly language, memory maps, and the obscure I/O ports of the Commodore chipsets.

That’s when I first met Eliza, the old chatbot that simulated a psychotherapist by reflecting your words back at you. Primitive — just pattern-matching and canned responses — but to me it felt like magic. The idea that a few lines of code could hold up a mirror to my thoughts was intoxicating. How does it work? How can it do this? I pored over its BASIC code, lost in endless chains of unreadable GOTO and GOSUB jumps.

I would sit for hours, typing questions, testing its patience. It didn’t matter that its answers were shallow — what mattered was the illusion of dialogue, the sense that something other was there on the screen, responding.

That summer, the seed was planted: the machine could talk back. And once a machine can talk back, the imagination can’t help but ask — could it ever mean it? Could it ever know it was speaking?

Act I – Pisa, 1991

It was one of those restless student nights in Pisa, between March and April of 1991, when the city’s medieval stones seemed to whisper old secrets as we wandered past them. I was 20, with a head full of half certainties and a heart drunk on the thrill of big questions.

There were three of us, but only two duelists. My friend Ste — sharp, logical, relentlessly rational — pressed me like a philosopher cross-examining a witness. I, by contrast, held tightly to my conviction: the brain was an algorithm, and consciousness its necessary output. Self-awareness, I believed, was wired into our biology as inevitably as wetness into water.

Ste wouldn’t let go.

“If the brain is an algorithm,” he asked, his voice cutting through the night, “and I write it down in a book, is the book conscious? If I arrange wooden sticks into a giant binary structure — zeros here, ones there — have I built a self-aware mind?”

We walked until dawn, past the leaning tower and the silent stone walls of the Lungarno, the debate looping like waves on the shore. I resisted, stubborn: No. It’s not enough to describe the structure. It has to run. Execution matters. To me, Ste’s book of symbols was like an old magazine filled with BASIC programs. Unless typed into a real computer, the code remained ink on paper.

By sunrise, I was left with more questions than answers. Somewhere deep inside, my mind was already screaming: there is a gap between structure and experience. But what fills it?

Act II – Early 2000s

A decade later, the duel returned to me unexpectedly, wrapped in a gift. Antonio, my friend and former CTO, handed me a book with quiet solemnity: The Mind’s I, edited by Douglas Hofstadter and Daniel Dennett.

Reading it was like entering a maze where every corridor opened to a mirror, and every reflection posed a different version of the same question: what is a self? what is a mind?

Some chapters unsettled me deeply.

There was Thomas Nagel’s What Is It Like to Be a Bat?. Nagel argued that no matter how complete our scientific understanding of echolocation becomes — down to every neural firing, every sonar map — we still would not know what it is like to be a bat. That first-person perspective, the subjective feel of “batness,” would always elude us. The essay forced me to confront the possibility that even a perfect structural model of consciousness might miss its essence: experience from the inside.

Then came the brain duplication paradoxes. Suppose my brain were copied perfectly, cell by cell, into another body. Would “I” wake up in both bodies? Only in one? Or in neither? If consciousness is purely structural, then the copy should be me — but how could “I” split into two? These thought experiments pulled at the thread of identity itself: was the self in the pattern, in the matter, or in something we didn’t yet have language for?

Hofstadter’s idea of the “strange loop” captivated me. He described the self not as a fixed entity but as a feedback loop, a system capable of referring to itself, building layer upon layer of self-representation until an “I” emerges. A loop so tangled that, in some sense, it creates the illusion of solidity. It was exhilarating — the thought that consciousness could arise from recursion — yet also unsettling, because if the self is a loop, then perhaps it is more fragile and less absolute than I had believed.

And then there was the dialogue Is God a Taoist?, which exploded into a meditation on free will. It presented a conversation between a seeker and a deity, circling around whether our choices are truly free or merely the inevitable outcomes of prior causes. For the first time, I saw how questions about consciousness cannot be separated from questions of agency. To be aware is not only to feel, but also to act — to live with the haunting sense that we could have chosen otherwise.

Taken together, these essays didn’t resolve the mystery for me. They destabilized me. They made me realize that what had felt like a neat computational certainty back in Pisa was in fact a wilderness of paradoxes — each one pointing to a blind spot in our understanding of mind.

And, like Antonio, I eventually came into the habit of keeping around two or three copies of this book, to hand out to fellow thinkers — a tradition I keep alive to this day.

Act III – 2022, The Age of GenAI

And then, two decades later, a day in November 2022, it arrived. ChatGPT.

At first it was shocking. I watched in awe at its ability to create sonnets, haikus, even a parody press release for the iPhone 666 written in the language of the Book of Revelation (hilarious — and disturbingly close in tone to Apple’s own keynotes!).

Then the questions started. If it moves like a duck and quacks like a duck, is it a duck? Not quite, but these things can now pass the Turing test. It is mind-blowing: we are living in science fiction.

But to me the real question has become: what does this actually say about the architecture of the human mind and how we store, process, and elaborate information?

Artificial intelligence today converses, creates, debates, surprises us. It executes patterns so vast and subtle that it can pass for real intelligence — well, most of the time at least.

But it is also easy to sense the absence. The words flow, the logic dances, the creativity sometimes startles — and yet there is no one inside, no “I”, no inwardness.

The question my friend Ste raised under the stars of Pisa has returned sharper than ever: if a brain is an algorithm, and we finally build it in silicon, will it feel? Or does consciousness require more than structure and execution — something only biology provides, something we don’t yet understand?

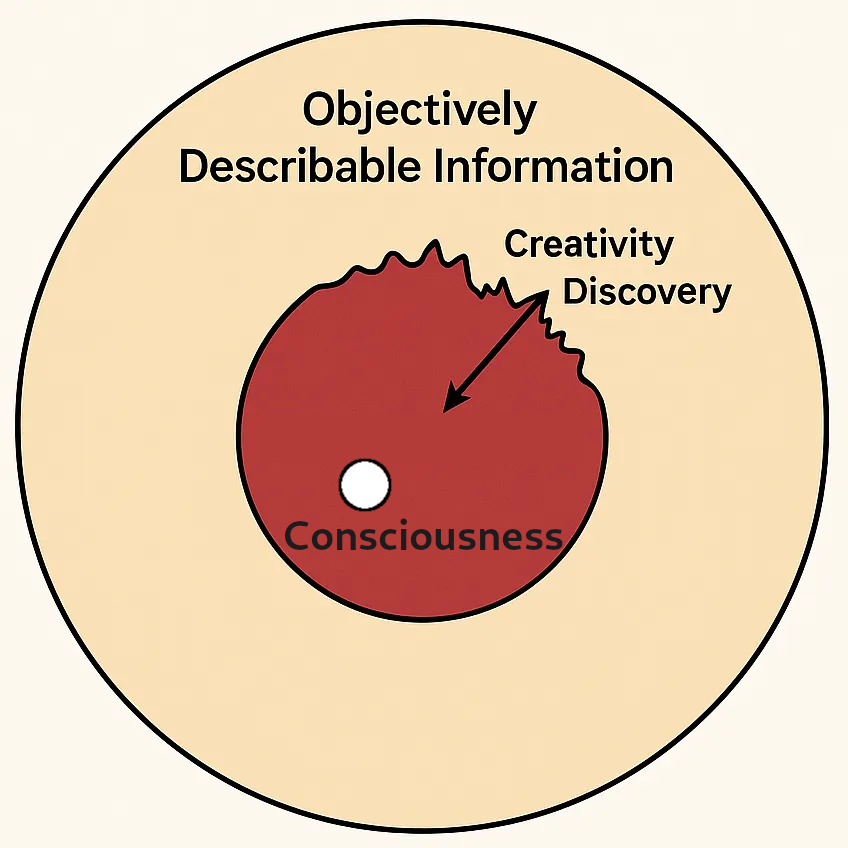

My impression is that consciousness does ultimately emerge from biology and structure, but I am not sure that we have yet reached a full understanding of how our own mind is architected.

Physicist Roger Penrose proposed the fascinating idea that the brain might function as a quantum computer, with quantum processes taking place in biological structures called microtubules. Many physicists reject this, arguing the brain is simply too hot and noisy to support quantum coherence, especially for error correction. Yet the analogy is striking: ideas often seem to appear suddenly, as if the mind were exploring many possibilities in parallel before collapsing into a single solution in an instant.

Penrose even goes further, suggesting that brains could act as “quantum antennas” tapping into a vast repository of shared ideas — a modern revisiting of Plato’s hyperuranium. I am not so sure about that last part, but I do feel the problem of mind architecture is still far from solved.

There are two main problems that I see about the architecture of the mind.

The first: human minds are not abstract thinking machines. We are embodied. We are deeply immersed in physical reality, and evolution has given us sensors — eyes, ears, skin, taste, nerves — to make sense of the environment around us. The whole conversation about qualia, those inexplicable physiological sensations, would make no sense at all without embodiment. Vision, the redness of a color, the taste of chocolate, a beautiful melody — these are all translations of the physical world presented to our brain. How does this affect our self-awareness? I do believe that the whole surrounding of our conscious mind is part of that architecture.

And most importantly: agency and free will. Today’s GenAI operates on inputs and produces outputs. There is no self-sustained process driven by an inner objective — survival, curiosity, self-improvement — that pushes it forward. There is no genuine ability to operate choices on its own, except those dictated by the recombination of its training data. Humans can escape the dictatorship of their own “dataset”; machines can’t. They don’t have agency, and they don’t have free will.

Is God a Taoist? Or, in modern times, is an LLM a Taoist?

Thirty years on, I still don’t have the answer. But the conversation continues — from the streets of Pisa, through the pages of The Mind’s I, to my daily exchanges with large language models. Perhaps the true “strange loop” is not in the machine, nor even in my brain, but in the way these questions keep circling back, refusing to settle.